DISCLAIMER: I’ve written about working for Major League Baseball in the past. Please note that while I use a baseball example for this topic, it does not represent how any internal MLB systems work.

Why Validate Data?

Any time you develop a system that handles user input, it’s important to validate that input to ensure whatever you’re storing isn’t “junk” or erroneous data. This can be extremely important depending on the purpose of the data’s1 existence. For instance, loss or degradation of data that’s used handling customer transactions or dealing with personally identifying information from users is going to be tolerated far less than perhaps recording log messages and other tertiary information. I’m not saying it’s “okay” to toss out this type of information, but it should make common sense that some kinds of data are more important than other data.

One thing that we’ve all experienced is that people become more error-prone as the speed of work increases. This can cause issues when a worker is time-crunched while inputting the type of sensitive or important data talked about above. Take for instance a healthcare worker that’s manually entering a medical record at a rapid pace – that’s definitely something you want to ensure accuracy of.

One way to do this is to insert data validations before this data can be saved, otherwise some prompt will be shown to the end user to allow them to correct their mistakes. Problem solved, right?

Maybe not. Let’s look at some fun baseball examples to see where this might break down.

Baseball is a Weird Sport

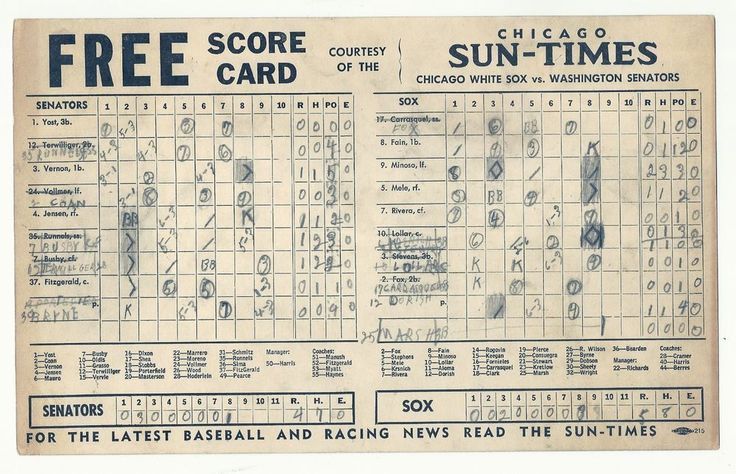

Let’s say we wanted to write an application that replaced paper scorecards for baseball games. A scorecard is a physical record of the game, down to who was playing which position, where balls were hit, what fielders were involved in plays, etc.

In order to do this, we’d have to codify the game of baseball – no small task, I assure you. For the purposes of this example, let’s just work on only the batting portion and see where some of our assumptions about baseball’s rules might break down.

Assumptions

- The state of the game will always conform to the official rulebook.

- General:

- There are 3 outs per half inning. After the third out, the fielding team bats, and the batting team assumes the field, unless the game is over.

- Batting:

- 4 balls result in a walk, and the batter assumes first base.

- 3 strikes result in a strikeout, and the batter is out.

- Foul balls count as a strike, but a batter cannot strike out on a foul ball.

- An at-bat always results in either a hit, an error, or an out.

But Are They Always Right?

Pictured: Blowing up your assumptions with the baseball grenade.

We can’t count on a single one of these assumptions to be correct 100% of the time.

The state of the game will always conform to the official rulebook.

Umpires are humans, and they make mistakes. When they make a call, their word is law, and any system that is tracking the state of the game should be capable of reflecting that. This is the most general of the assumptions, and all the others can be lumped into this category.

There are 3 outs per half inning. After the third out, the fielding team bats, and the batting team assumes the field, unless the game is over.

There can be a fourth out. It’s a weird and quirky rule, but one that can have drastic impact on the game.

Similarly, there has been talk of a catch-up rule to shorten the game times. Basically, if a team scores a go-ahead run, they would only get two outs instead of the normal three.

4 balls result in a walk, and the batter assumes first base.

There was a five ball walk in 2015, the very same year we also saw a three ball walk. It has no doubt happened many other times.

3 strikes result in a strikeout, and the batter is out.

Unless the catcher drops the third strike, in which case the batter is free to attempt to reach first base before he can either be tagged or thrown out. If he reaches first base, it’s still a strikeout, but no out.

Foul balls count as a strike, but a batter cannot strike out on a foul ball.

Unless the batter foul tips the ball, and the catcher does not drop the ball.

An at-bat always results in either a hit, an error, or an out.

Not always. It can be ruled as reaching on a fielder’s choice, or when there’s already a runner on base and the defense attempts to get the existing runner out before the batter. The batter reaches base successfully, but it is not ruled a “hit”.

Validating an At-Bat

Whew! So we’ve seen how even well-intentioned assumptions can break down when we try to actually codify them. And this is just a subset of the game! This can obviously get much more complicated if we’d let it. Instead, let’s worry about writing some data validations for an at-bat only. For our purposes, we’re only interested in the pitch count and validating that they could actually exist.

In Rails, we might set up a data model that looks something like this:

class AtBat < ActiveRecord::Base

has_many :pitches

validates_with PitchCountValidator

end

class PitchCountValidator < ActiveModel::Validator

def validate(record)

if record.pitches.balls > 4

record.errors.add :base, "Can't have more than 4 balls, got: #{record.pitches.balls}"

elsif record.pitches.strikes > 3

record.errors.add :base, "Can't have more than 3 strikes, got: #{record.pitches.strikes}"

elsif record.pitches.strikes >= 3 && record.pitches.balls >= 4

record.errors.add :base, 'Invalid pitch count for at-bat, cannot strikeout and walk at the same time.'

end

end

end

class Pitch < ActiveRecord::Base

belongs_to :at_bat

scope :strikes, -> { where(type: :strike) }

scope :balls, -> { where(type: :ball) }

enum type: [

:ball,

:strike,

:foul,

:in_play,

:hit_by_pitch,

# etc...

]

end

You might say, “Tyler! There’s a bug in this code – you aren’t looking at foul balls in your validator!”, and you’d be right. It’s not really important for the purpose of this example, though. It’s obvious looking at this code that we’d expect a validation error if we tried the 5 ball walk, even though we can clearly see that is a “valid” game state that occurred. We can probably say that implementing this type of validation would make the game harder to score for some small number of cases.

When Is Too Much, Not Enough, or Just Right?

You’ll need to decide what is priority for your use case – do you need “clean” data 100% of the time, can you afford to enforce strict validation, and do you have the resources available to be able to fix issues quickly if they need to be escalated to support or help desk staff? If not, you may be better off looking at what assumptions aren’t safe to codify and work towards allowing an acceptable level of data entry errors.

It’s important to think about. Make your validations too strict and it can bottleneck your users or block processing by dependent systems, requiring developer intervention to resolve (mainly by temporarily loosening validations or altering data to fit inside the system’s pre-conceived notions). Make them too loose, and you risk needing a manual data quality analyst to check the validity of your data or risk having the vast swaths of data be complete junk.

In the meantime, I’ll keep thinking about how weird baseball is.

EDIT (8/23): If you like reading about these developer assumptions, here’s a whole GitHub repository full of common misconceptions developers can fall into.

That’s all for now. Thanks for reading!